What Ingo Swann Taught Me About His Ideograms

by Tom McNear

- Introduction

- What Is an Ideogram?

- Ideogram Sequence Part One: The Ideogram—the I-Component

- Ideogram Sequence Part Two: The Feeling-Motion—the A-Component

- Ideogram Sequence Part Three: The Automatic Analytical Response—the B-Component

- The Ideogram Sequence (I + A = B)

- Ideograms: A Lack of Understanding?

- What Did Ingo Swann Teach About the Ideogram?

- What Did Ingo Swann Teach Me?

- Did Ingo Swann Conduct Ideogram “Drills” With His Students?

- What Did the CRV Manuals Say About the Ideogram?

- CRV by the Numbers

- Summary

Introduction

The ideogram is perhaps the greatest insight of Ingo Swann. It seems simple at first, yet may be the most exquisite and least-understood concept of Ingo Swann’s teachings on Controlled Remote Viewing (CRV). In my three years of study with Swann I learned a lot from him, which I will share with you here.

It may seem strange, but as simple as the ideogram itself appears to be, this very simplicity may be what makes it so hard to master. Many inexperienced viewers quickly grasp what they believe to be the basics of the ideogram, then think to themselves: “I’ve got it; that was simple. Time to move on to the higher stages of CRV.” They want to start sketching. They want to experience the site in almost mystical ways. They want to name the target. Often it is this desire to rush into remote viewing’s higher stages that prevents them from truly mastering the apparently simple complexity of the ideogram. Yet, it is understanding this that will allow them to successfully advance into remote viewing’s higher stages.

Swann taught that the ideogram represented the gestalt of the primary aspects of the target, and provided all the information necessary to understand it. This information is in an encoded form; the remote viewer, working through the stages of CRV, decodes the information that the ideogram initiates.

The ideogram you could think of as being like the cover of a book lying on a table. Yes, by looking at the cover one can learn the basics of what is contained therein. Is it a biography or a science book? Is it about ancient history or about space exploration? If this rudimentary understanding is all one seeks, there is no need to open the book and read it.

Likewise, if one only wants to know the basics of the site—Is it land or water? Is the target a structure or a natural feature?—an in-depth understanding of the ideogram may not be necessary. But if the viewer wants to know more, then understanding the complexity and the intricacy of the information initiated by the ideogram is essential.

I call this paper Ingo’s Ideograms at the Master’s Level, because truly understanding the way it was taught by Ingo Swann will help ensure valuable information about the site is not lost by racing prematurely into the higher stages of remote viewing. Those who prematurely move beyond the ideogram will surely fail to recognize the depth of the information the initial ideograms make available.

As I said, in this document I’m sharing what Ingo Swann taught me about ideograms. I emphasize me because I can’t speak to what and how he may have taught others who came after me. I also emphasize that I am writing about what Ingo Swann taught, not what others may teach. It is not my intent to enter into a discussion of what others may teach. But I hope many can learn from Ingo Swann’s brilliance. [1]

I will begin with what Swann taught and did not teach about the ideogram, but I will also address the questions frequently asked by viewers, often by long experienced viewers. Perhaps in gaining more in-depth knowledge viewers will share what they learn here with others in the RV community, especially beginning viewers. Let’s get them off to a great start in CRV.

One frequently asked question is, “Did Swann change what he taught or how he taught?” Let’s address this question up front. While Swann likely used different words or phrasing from one student to another, what he taught remained the same. Swann was highly intuitive and could tell if his students clearly understood the points he was making. If he perceived his student needed further explanation, he might use a different word or expression to ensure the student’s understanding, but as for what he taught his students—it was the same.

Where did the concept of the ideogram originate? Let me begin by quoting my friend and colleague Paul H. Smith. In a 2001 document entitled Ideograms, Paul wrote:

Over the years, Puthoff and Targ had a neat way of dealing with reporters, scientists, and government officials showing up at SRI demanding proof that remote viewing really worked. Instead of trotting out some stellar remote viewing performer whose success would be doubted even if demonstrated under the very nose of the questioner, visitors were challenged to try it themselves. Many of them accepted the challenge, and most of them were successful. All these sessions done by people “right off the street,” amounted to more than 140 remote viewing trials that were useful as scientific data.

In looking over this pile of RV transcripts, Ingo noticed something peculiar. Both experienced and inexperienced viewers were encouraged to remote view with pen and paper in hand, to record their impressions in word and sketch during the session. But nearly every time someone launched into remote viewing, he seemed to have the urge to make a little scribble on the paper when first contacting the signal line. Ingo found something familiar about the behavior, and the scribbled results it left. One day it suddenly dawned on him—it reminded him of a chapter in Arnheim’s book, “Art and Visual Perception”, which Ingo had first read when studying art in college. Arnheim had looked at how young children first approached art, and what role their newly developing perceptual abilities played. When first learning to capture on paper the things around them, young kids made scribbles that were very similar to those of remote viewers. It was as if the children were intuitively trying to grasp the essence of the subject they wanted to draw. Essence is closely akin to—perhaps identical with—the notion of gestalt. Ingo wondered if perhaps these little scribbles were the initial apprehension of the major gestalt of the target. After experimenting with the concept, Puthoff and Swann decided that indeed the scribble was a primitive representation of the target’s gestalt. Seeking a word to call it, they happened upon “ideogram,” which means basically a graphic mark or sign of some sort that stands for an object or idea.

In December of 2010, Ingo Swann stated, “The first thing that goes downhill in RV is (that) people don’t understand the ideogram.” [2] Even experienced viewers sometimes forget the significance of the ideogram. In doing so, they fail to recognize it is the initial ideogram(s) that establish the foundation for the rest of the session. Swann taught that the initial ideogram represents the primary gestalt of the target and contains, in an encoded form, all necessary information needed to understand the target in its basic nature. By decoding the information contained in each ideogram, viewers will have the firm informational base necessary to progress to more advanced CRV stages.

How is a remote viewer tasked, targeted, or “sent” to the location of interest?

The term for this tasking is a target reference number (TRN) or just tasking number (TN). A TN is a coordinate or random number used to identify for the viewer the desired location of interest. Almost any reference can be used to task viewers providing the tasker’s intentions are associated with the reference. The tasker and the viewer both implicitly agree that the TN indicates the target and the information the tasker seeks about that target. Just how the tasker’s intentions become linked or entangled with the desired target is all part of the mystery of CRV and is far beyond what is covered in this document. Just as the tasking number represents the target in the minds of the tasker and the viewer, likewise the ideogram represents the target in another form.

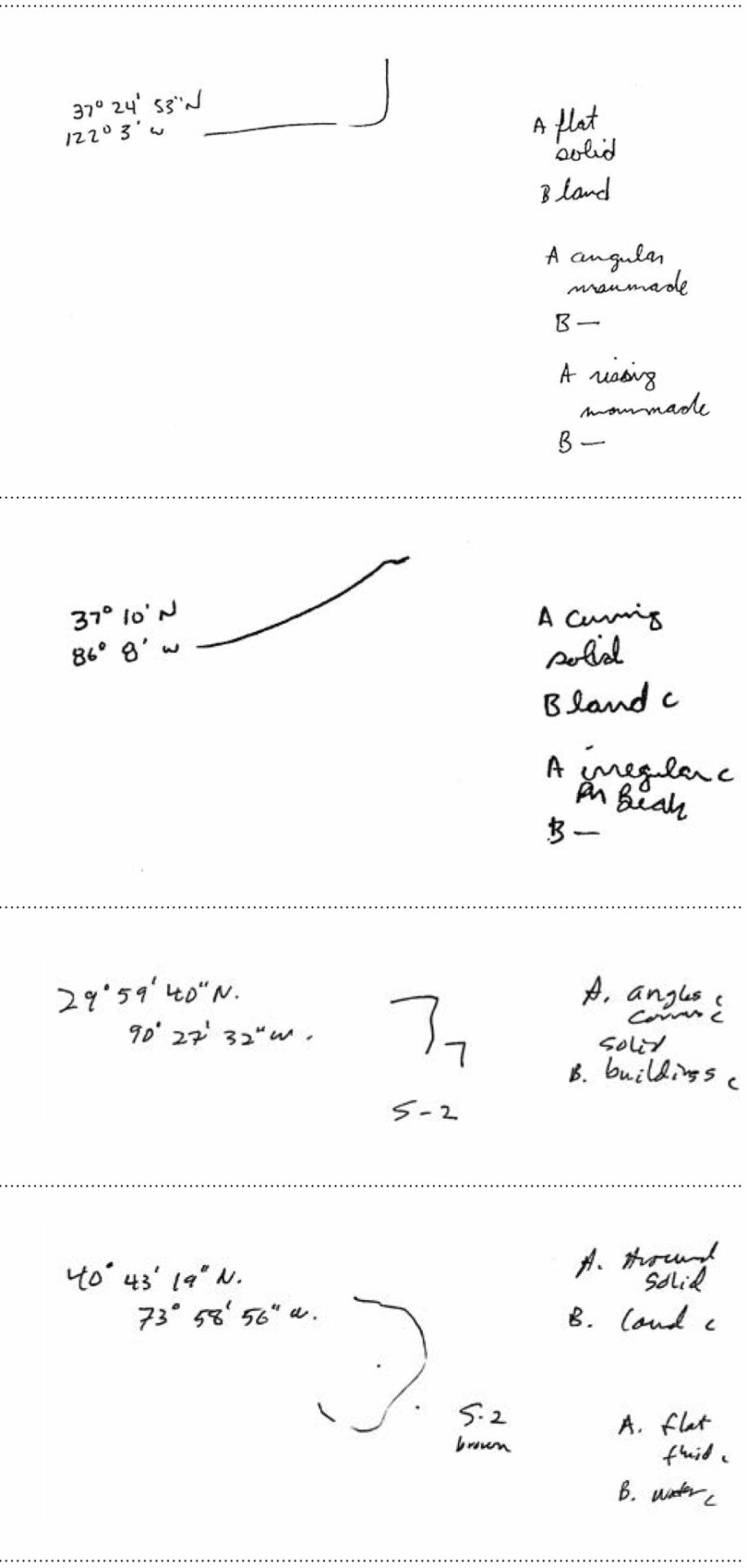

During early CRV training with Swann the tasking number was simply the geographic coordinate of the physical location on Earth expressed in degrees, minutes, and seconds. This was one reason why CRV was initially known as Coordinate Remote Viewing (CRV). CRV was later changed to Controlled Remote Viewing—still CRV—and geographic coordinates were no longer used. [3]

Instead, arbitrary numbers or even sealed envelopes replaced the use of geographic coordinates. Why? There were several reasons. CRV skeptics often charged that viewers weren’t really viewing, they had simply memorized all the coordinates on the face of the Earth and were merely describing the target from memory. Actually, this would probably have been a feat greater than remote viewing itself. Additionally, using geographic coordinates sometimes confounded the viewer; from the coordinates, they could often recognize the general area of the world the coordinates represented, causing the analytical mind to “try to help” by offering “suggestions” as to what the target could be. Switching to sealed envelopes or randomly selected numbers alleviated these concerns. An added benefit was that it allowed remote viewers to be tasked on targets whose locations were not known, such as people or events.

Ltc Tom McNear

There are two other terms readers must understand before reading further: site and target. The site is the general vicinity in which viewers find themselves after receiving the tasking number. The target is the actual object or event the viewer is being asked to describe. The site may be The White House in Washington D.C., but the target may be the President of the United States who resides within the site. The site may be a specific location, but the target may be an event occurring at that location. The site may be Pearl Harbor on today’s date, but the target may be Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Typically, sites are locations, while targets may be locations, people, events, or times. While they may appear to be interchangeable, and sometimes they are, I will endeavor to use the appropriate term at the appropriate time throughout this document.

In Paul Smith’s previously cited Ideogram document, he mentioned Swann’s concept of the signal line. Swann described the signal line as a sequence of signals that emerge from the target. I like to describe this sequence as an oncoming freight train. Upon receiving the tasking number, information about the target is aligned and presented to the viewer in sequence much like a train on its tracks—freight car after freight car or ideogram after ideogram. The initial ideogram usually represents the primary gestalt(s) of the target (the locomotive). When this ideogram is correctly and completely decoded (more about decoding later), subsequent ideograms may present themselves providing additional, more detailed information about the target. Swann’s friend, Robert (Bob) Durant, called the process “the relentless progression of the data.” There’s no better way to describe it.

Because Swann taught that ideograms are sequential, he taught his students to receive the initial ideogram, decode it, then take the tasking number again ready to receive the next ideogram containing refined details about the site. Some RV schools teach a process where the viewer may receive a long, elaborate ideogram that may represent many aspects of our “freight train.” After objectifying the ideogram, the viewer then assesses the ideogram for changes in feeling along the length of the ideogram. It may start as a solid feeling of flat land, change to a fluid feeling of water, and then change again to the feeling of manmade. At each point where the feeling changes, the viewer places a small mark and objectifies the changes in feeling—objectifying a feeling and an analytic assessment for each portion. As taught by Swann, these three features, in this case, land, water, and manmade would likely each present as separate ideograms.

Swann taught to never add to the ideogram after it was received and objectified. While he and I never discussed the “segmenting” of long ideograms, I feel certain he would question this practice. He would ask, “How does the viewer know whether the additional marks are a part of the original ideogram or part of the analytical function of dividing the ideogram into its various parts?” [4] Perhaps practitioners of this extended ideogram learn how to make use of the sectioning marks without it interfering with their decoding of the ideogram, but this was not what Ingo Swann taught.

What Is an Ideogram?

Remember, Swann said: “The first thing that goes downhill in RV is [that] people don’t understand the ideogram.” Before moving forward, one must clearly understand what the ideogram is. The appearance of an ideogram can be described as a “scribble,” or a “squiggle on paper.” The graphic portion of the ideogram sequence is the ideogram. The ideogram is the first spontaneous, graphic representation on paper of the major gestalt of the target. It is an almost involuntary, kinesthetic, feeling-response to encountering or contacting the signal line. Some compare the production of an ideogram to what is known as automatic writing. The ideogram produces itself in response to receiving the tasking number with little help from the viewer. I stated the ideogram is almost involuntary; if a viewer resists producing an ideogram, none will be produced, but if the viewer cooperates with the feeling, the ideogram is spontaneously produced with little thought or effort from the viewer.

Just as Arnheim discovered, the basic scribbles of children frequently captured the basic forms and shapes of the items they were sketching, Swann also recognized the initial “scribbles” of beginning viewers often resembled these same basics. When asked what the scribble represents, viewers often respond with, “I don’t know,” “it was spontaneous” or “it just felt right.” It was this sense of feeling that lead Swann to discover what he called the feeling-motion—but more about that later. Arnheim recognized this sketching to be an innate ability in children that required neither tutoring nor instruction. Likewise, Swann discovered that beginning viewers required little guidance or instruction to produce ideograms: he believed it to be an innate reflex we all possess. He determined it was the feeling-motion that motivated the hand/arm to produce the ideogram.

Because the feeling-motion produced the ideogram, his emphasis was always on capturing the feeling-motion rather than on the graphic appearance of the ideogram. Sometimes, beginning viewers believe they can look at the ideogram and determine the target, but relying on the visual appearance of the ideogram will almost surely lead to failure. This is generally because the ideogram was produced by the viewer’s near-automatic response to the feeling-motion of the target (see feeling-motion below), and because the viewer initially may have no understanding of the perspective from which they are engaging or viewing the target. Is the curving ideogram a dome-shaped structure as viewed from ground level, or is it the curving shoreline of an island as viewed from above? While receiving the ideogram, the viewer has little awareness of this perspective or viewpoint.

Most viewers think of the ideogram as just the squiggle or the ideogram, but the complete ideogram sequence as taught by Swann consisted of three parts, 1) the squiggle or ideogram, 2) what he called the feeling-motion that caused the ideogram to be produced, and 3) the automatic analytical response to the synergy of the ideogram and feeling-motion. Three parts, not one. We will now take a closer look at each of the three parts of the ideogram sequence.

Ideogram Sequence Part One:

The Ideogram—the I-Component

The graphic portion of the ideogram sequence is the ideogram. As previously mentioned, many consider the ideogram mark to be the ideogram in its entirety; this is an easy and common misperception. For many of us, our visual sense is our dominant sense. “I see things more clearly now” or “Look at it this way” are common phrases. When we hear a sound, we often try to visualize what it is that could make such a sound. So when one looks at a remote viewing transcript and sees the ideogram on the page, they believe THAT is the ideogram. Many beginning viewers also look at the ideogram and think they are seeing the target, thinking the ideogram is a sketch or drawing of the target. This is wrong; why this is wrong will become more clear as you read on.

Swann said that no two ideograms “look” the same. Each is representative of a specific target. Just as structures and landforms can have millions of shapes, so can the ideograms representing them. Is the structure dome-shaped, tall and thin, or underground …? While the ideogram may not look like these shapes, they represent these structures in a right-brained, subconscious sort of way.

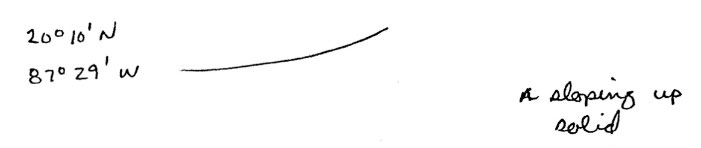

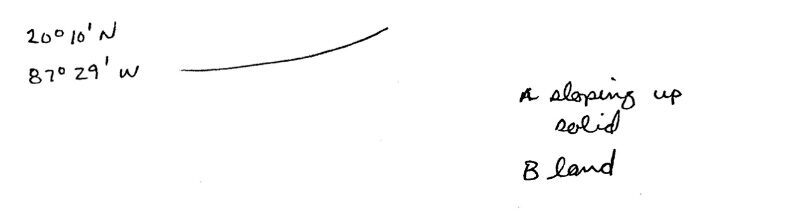

Below is an example of a basic ideogram [The ideogram examples in this article are taken from Ingo’s training folders.]:

Some viewers believe the ideogram should or does “look like” the target and they place great weight on its physical or graphic appearance. Ingo Swann said, “Don’t look at the ideogram and expect to see something in it.” Why he said this will become clear; but he didn’t say, “Ignore the visual aspects of the ideogram”; why would he? The viewer produced the ideogram. They saw the pen produce the ideogram on paper. Of course, they know what the ideogram looks like; for them to try to “unsee” its physical appearance would cause confusion—not a good way to begin a remote viewing session. The physical appearance of the ideogram is definitely a component of the ideogram sequence that the viewer will incorporate in the viewing process, but the viewer’s focus must be on the feeling-motion. So what is the feeling-motion?

Ideogram Sequence Part Two:

The Feeling-Motion—the A-Component

The term feeling-motion is not a term in common use. Swann taught that the ideogram was produced by what he called the feeling-motion. This feeling-motion is one thing, not two. He said that there was no word in the English language that simultaneously encompassed both feeling and motion so he developed the phrase, and the concept, of the feeling-motion. The viewer experiences the feeling while producing the ideogram. These feelings represent the consistency of the target and the feel of the target as if the viewer were physically at the site. These feelings are expressed as adjectives. Viewers experience such feelings as hard, fluid, liquid, soft, manmade, etc. Because of the open construction of the Eiffel Tower, viewers might describe it as airy. But these feelings are only the first part of the feeling-motion.

While producing the ideogram, the viewer is experiencing the feeling, but they are also experiencing the motion. This motion is often described as the motion of the pen on the paper as the viewer was producing the ideogram, but it is more than that. The motion emanates from the target, and this motion motivates the viewer’s muscles and nerves to move the pen in such a way that it produces an ideogram that represents the main gestalt or contours of the target. Did the motion move horizontally across the page? Did the motion go up or down? This motion is the second part of the feeling-motion. Up, down, wavy, erratic, diagonal, or across are examples of the motion the pen might take and the viewer might experience. Viewers may also experience motion at the site, such as rapidly moving, expanding, moving up and down, etc. The viewer’s ability to accurately perceive and characterize the motion improves with experience.

A complete feeling-motion accompanying the production of the ideogram then might be fluid wavy or rising solid. The feeling and the motion can present in either order, the importance is to capture both sensations and not to worry in which order they present. It is the feeling-motion that caused the creation of the ideogram, and it is the synergy of both the feeling and the motion that conveys significant information to the viewer.

Ideograms are the viewer’s kinesthetic response to the target. Viewers, through the feeling-motion, feel and experience the target. The feeling-motion precedes the ideogram because the feeling-motion produces the ideogram. [5] The feeling-motion causes the viewer’s hand and arm muscles to move in response to contact with the target. This response is pre-conscious and is initially not intelligible to the conscious mind; the muscles know, but the conscious mind does not. Because the feeling-motion preceded the ideogram, the viewer must focus on the feeling-motion, not the physical characteristics of the ideogram as it exists on the paper.

What Swann called the feeling-motion, RV instructor Paul H. Smith calls the motion-feeling because the viewer typically experiences the motion first, before the feeling. While Paul reverses the term, his teaching of the feeling and the motion is identical to that of Ingo Swann, and, as stated above, the feeling and the motion can present in either order.

After producing the ideogram, the viewer will write an uppercase letter A (see below). Following the letter A, they will write the feeling-motion they experienced. This “objectifies” the feeling-motion.

While the feeling-motion may appear to be two things, the feeling and the motion are experienced nearly simultaneously and can be thought of as one unified experience. I like to use the example of riding in a canoe. Riders in a canoe experience the calm feeling of floating and flowing with the motion of the canoe, but when a motorboat passes by, they suddenly experience the feeling of the canoe rising and falling, and rocking side to side. They feel the feeling and their body experiences the motion of the canoe simultaneously. If at that time, the rider in the canoe had a pen on paper, I feel certain they would produce an ideogram that contained or expressed both the feeling and the motion. Simple.

Ideogram Sequence Part Three:

The Automatic Analytical Response—the B-Component

After the viewer has produced the ideogram and objectified the feeling-motion behind the letter A, next comes the viewer’s automatic analytical response to the target. The automatic analytical response is the spontaneous response of the viewer to the ideogram and the feeling-motion; there is synergy when the two are taken together. The viewer felt the feeling and experienced the motion; from this, their intuition may give them an immediate general idea of what the site might be. Until this point, the viewer was encouraged to use only adjectives to describe their perceptions. The automatic analytical response is a noun representing the viewer’s “spontaneous analytical” response to the ideogram and the feeling-motion. This response is immediate, fast, and effortless. I call this a right-brained analysis—what Swann called “an analytic judgment within the subjective or intuitive process.” [6]

Is it land, is it water, is it a structure? While viewers may perceive other nouns, these are the broad categories that typically present after the ideogram and the feeling-motion. After objectifying the feeling-motion as the A, viewers will write an upper case letter B (see below). This B prompts the viewer to make the quick automatic analytic response.

The sequence is I + A = B. This analytic response must be quick and automatic without overly engaging the left-brained analytic mind; hesitating or pausing too long can allow the analytic left-brain to jump in and “try to help” by submitting analytical ideas for the viewer’s subconscious to consider. If there is no automatic response, the viewer should simply state there is no B and take the tasking number again to once again begin the I + A = B sequence.

The A component is a description of the experience of initially encountering the target in psychic space; the B is a statement of what the target is, in gestaltic terms. Any time viewers begin wondering to themselves what the target might be, the analytical left brain will surely provide an answer and create confusion or “analytical overlay” (AOL). Analytical overlay is the left brain trying to make sense of the fragmentary data received during the ideogram process; these impressions come from imagination or memory.

Viewers might also intuitively incorporate the visual aspects of the ideogram into this response, but the visual aspects of the ideogram are secondary to the feeling-motion. AOL may sometimes be correct, but often this overlay leads the viewer away from the signal line and into imagination.

The Ideogram Sequence (I + A = B)

After objectifying the noun that represents the target (the B) the viewer has completed CRV Stage 1. While Stage 1 often provides just the basic perceptions of land, water or structure, it is the most important stage of CRV because it is the foundation for all subsequent CRV stages.

The initial ideogram perceived by the viewer typically represents the primary gestalt of the site or target. Once this ideogram has been processed or decoded through the CRV process, subsequent, different ideograms may present themselves. These subsequent ideograms likely pertain to different aspects of the site. For example, if the site is a barn in the middle of a grassy field, the viewer may receive both gestalts in a multiple ideogram, or may receive one ideogram representing the barn and a subsequent ideogram representing the grassy field. These subsequent ideograms are rarely received until after the initial ideogram is accurately and completely decoded (unless that’s all that is present, such as the middle of an ocean). If the same ideogram repeats itself, this indicates that the viewer has incompletely or inaccurately decoded the ideogram. Once the ideogram has been correctly decoded, subsequent ideograms may be produced.

Different ideograms may present themselves for the same target. Swann believed the ideogram contained all of the information necessary to understand the target. For example, there are many structure shapes or styles and there is no “one correct” ideogram to represent them all. As stated, ideograms come from the target, not the viewer’s mind. Different ideograms may take on physical characteristics of the target, i.e., curving or straight, underground, low and broad, or soaring; these characteristics are felt in the feeling-motion and are often graphically portrayed in the ideogram.

When the same viewer is tasked against the same target, they may often produce a different ideogram with each tasking. One ideogram may represent the target from one perspective, on the ground in front of the building, for example, but the next ideogram may represent the same target from the side or from above. These two different perspectives will likely produce different ideograms representing the same target. This is common.

Additionally, “similar looking” structures may have an entirely different feel to the viewer. This is due to the feeling of the structure and not the appearance of the structure. A church, a school building, or an official government office building, while all may have similar visual appearances, they may feel very different to the viewer. These differences will become clear in the more advanced stages of CRV, but in focusing on the graphic appearance of the ideogram, the viewer is likely to lose the appreciation of these advanced feelings emanating from the target. Swann was adamant that viewers should focus on the feeling of the ideogram and not its graphic or visual appearance. While it’s true that the ideogram can often look like the physical appearance of the target, the ideogram usually feels like the true characteristics of the target.

With this understanding of the ideogram sequence, its three parts (the I, the A, and the B), and the importance of the feeling-motion in decoding the information contained therein, let me address why the ideogram is not better understood.

Ideograms: A Lack of Understanding?

If there is ambiguity in understanding the ideogram, why? One possible cause, Swann followers please forgive the heresy, may lay with Ingo Swann himself. When Swann was teaching me from 1982 to 1985, he wrote little about the ideogram; much of the instruction he provided was verbal. Below is perhaps Swann’s most detailed description of the discovery and development of the ideogram. Swann stated he saw what later became known as “ideograms” in the works of many early “psychics.” I will let Ingo speak for himself.

The concept of the “ideogram” began coming into view in about 1974, and it was my humble self that first recognized its importance—because in my early art research and studies I had read the first 1954 version of a book entitled “Art and Visual Perception—A Psychology of the Creative Eye” by Rudolph Arnheim (a new version of this book was published in 1974). Arnheim also produced a book entitled “Visual Thinking”. Now, what we were referring to as “doodles” (i.e., an aimless scribble, design or sketch) had over frequently been turning up in experimental sessions produced by many dozens of volunteers, and which had been considered as some kind of “noise.” So I finally asked: “What are all of these doodles doing in this stuff?”

Arnheim doesn’t particularly identify these doodles as ideograms, but plenty of them are illustrated in his book—as “something that STANDS [his emphasis added] for the idea of something,” especially in the cases of children who can’t otherwise draw the something more completely or accurately. Hal [Puthoff] and I decided to refer to these doodles as “ideograms” defined as a picture or symbol used in an information system to represent a thing or idea; especially one that represents not the object pictured but some thing or idea that the object pictured is supposed to suggest.

This was sort of shocking at the time. For it implied that the RV process was a creative gestaltic artistic one from the bottom up, and not an intellectual linear one at all. Much to your credit you seem to have recognized this on your own, but as time soon proved few others can do so (or even want to). Indeed, if we had not had numerous perceptual psychologists in our equally numerous oversight committees who understood this, our project would probably have been quietly terminated. [7]

Swann doesn’t say so in this correspondence, but he is quoting almost word for word the Merriam-Webster definition of “doodle,” which is “an aimless or casual scribble, design, or sketch.” Obviously, Swann realizes that ideograms are more than “doodles.” He tells us that Arnheim himself refers to “doodles” as standing for the idea of something (though a search of Arnheim does not show that wording, rather Arnheim refers to “doodles” as graphical elements created absentmindedly which are “more often just chance agglomerations of elements” [Art and Visual Perception, p. 149, 1974 ed.]; Swann may be confusing his memory of “doodles” with some other passage in Arnheim’s book, where Arnheim does talk about purposeful children’s sketches—which he does not refer to as “doodles”—as representing the “idea” of what the child perceives). But we are dealing with Swann’s words here, not directly Arnheim’s, so in the letter quoted above, Swann mentions an ideogram as “a picture or … a symbol … that represents a thing or idea …”

Ingo Swann and Tom McNear, New York, 2011

This at least distinguishes an ideogram from a doodle in that, to the perceiving person, an ideogram expresses meaningful content, whereas a doodle (“more often just chance agglomerations of elements”) does not. Unfortunately, Swann’s description still retains some ambiguity. “Symbol” can, of course, refer to anything from a simple abstract graphical element (such as a corporate logo) with little intrinsic representational appearance, to a recognizable representation in the form of an icon, a caricature or even a realistic pictorial image—to even a physical object. I believe in this letter Swann doesn’t mean us to take the word “symbol” too rigidly, and that he is using “doodle” figuratively, referring to an ideogram’s superficial resemblance to more mindless squiggles like doodles on a scrap of paper, but not at all implying that an ideogram is as empty of content as is an actual doodle.

This is confirmed by his remark that coming to understand ideograms helped lead him to the realization that the remote viewing process is “a creative gestaltic artistic one from the bottom up,” which rules out the possibility that ideograms bear any similarities to doodles beyond a mere superficial resemblance to those who are unaware of what ideograms are.

So, as readers can clearly see for themselves, even Ingo Swann could occasionally be imprecise with his wording. Perhaps this has contributed to a lack of understanding.

What Did Ingo Swann Teach About the Ideogram?

One of the problems this question brings up is that Swann had never documented his formal training program—no known textbooks, formal written notes nor slides. So in order to get a reliable definition, you have to seek the answer from someone with firsthand experience in learning directly from Swann himself.

Ingo Swann & his military students, 1984

Tom Bergen, who was the final person trained by Swann from 2004 to 2012, confirmed that as late as 2013, Swann appeared to have no training notes or manuals, “just some slides from the SRI training days” (1982–1984).

Many have read documents from Swann’s archives and have used his written notes to try to understand his views on the ideogram. Some have even cited the training notes and essays of Swann’s students to support their views. Their “interpreting” of these notes has sometimes led to some of the confusion. On the subject of the ideogram, Swann spent days and weeks explaining his views to his students. Though he taught the ideogram during CRV Stage 1, detailed discussions about the ideogram continued throughout all stages of CRV training—for me, all the way through Stage 6 training. These long, in-depth discussions cannot be reduced to the few notes one might find in his archive. Indeed, it is difficult for me to capture such depth in this document.

To emphasize the importance of the ideogram, regardless of the CRV stage, below I quote my CRV Stage 6 daily report. On 3 Jul 1984, I was training with Ingo Swann on Stage 6. Surely by Stage 6 I should have fully grasped the importance of the simple ideogram, but in that day’s daily report I wrote:

I relearned for the 100th time the importance of fully interpreting (decoding) the ideogram. The ideogram is the basis for the entire signal line. The ideogram contains all the basic elements needed to acquire the site. Ideograms are important. Ideograms are important. Ideograms are important. Ideograms are important …

If you don’t completely interpret (decode) the ideogram, four things will happen: 1) you won’t get the content of the site, 2) you will not progress into the more difficult aspects of the site, 3) you will produce many AOLs, and 4) you will go into AOL drive.

As you can see from my Stage 6 report, the ideogram never loses its importance to the remote viewing process no matter what stages the viewer has achieved.

There are many ways to teach remote viewing, and there are other forms of remote viewing than Swann’s Controlled Remote Viewing. I have no qualms with those who may be teaching differently from the Swann method. I know some very effective viewers who have learned from those instructors. With certainty, I can say that some of the other methods are producing capable viewers, but we must recognize these are not the methods of Ingo Swann. Why is this important? We students of Ingo Swann simply want to keep the historical record straight. Today, the CRV community is studying the historical records of luminaries such as Rene Warcollier or Upton Sinclair. What if, back in the day, others attributed to Warcollier teachings that were not his own? Today, we would not have an accurate picture of Warcollier’s true contributions—what he got correct and where he may have been inaccurate. If today, we in the RV community are doing the same to the teachings of Ingo Swann, how will future generations be able to accurately understand his true contributions?

I applaud those who are successfully teaching other methods, but please don’t attribute those ways to the teachings of Ingo Swann. Various practitioners and instructors have developed their own ideogram techniques; they should not be criticized for that. If their teaching techniques are working for them, they should be happy with that success. They should put their names to their techniques and call them their own. But please don’t confuse the historical record by inappropriately attributing them to Ingo Swann. As I write this paper, Ingo Swann “is the history of RV and CRV.” One hundred years from now, many of our contemporary CRV instructors may be the “new history of CRV.” The record must remain accurate and their stories should be told. It is this accuracy I seek in writing this document.

I was trained by Ingo Swann from 1982 to 1984. For the first few months, my friend and colleague Robert (Rob) Cowart and I trained directly with Ingo Swann. Unfortunately, Rob was soon diagnosed with cancer and was medically retired from the Army. From that point forward, for the next three years, I received my training one-on-one from Swann.

As I was the “prototype” for this training and Swann knew others would follow, he spent much of his time with me seeking to develop and improve the delivery of CRV training. He would ask, “How was that?” or “Could I have presented that differently?” Because of this, I believe he may have made small changes in his delivery or in the particular wording he chose, but after many years of discussions with his other students who came after me, I feel certain he did not change what he taught.

What Did Ingo Swann Teach Me?

Swann was highly intuitive and could tell if his students clearly understood the points he was making. If he perceived his student needed further explanation, he might use a different word or expression to ensure the student’s understanding, but as for what he taught his students—it was the same.

Ingo Swann knew the significance of words. He frequently said that “words are mind-traps” and that precision in word choice was essential in avoiding ambiguity leading to confusion. The words he used in teaching CRV were often unique: before being involved in CRV, who had heard of remote viewing, ideograms, feeling/motions, etc? These terms can be interpreted in several ways. Even more common words can also have multiple meanings; if the instructor and the student are not in agreement with the actual meaning of a given word, training may fail due to the “mind traps” of which Swann spoke. For this reason, each of Swann’s students was handed a Merriam-Webster (M-W) dictionary at the beginning of class. Let’s see what Merriam-Webster online says about the subject of this document: ideograms.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines ideogram as:

a picture or symbol used in a system of writing to represent a thing or an idea but not a particular word or phrase for it; especially: one that represents not the object pictured but some thing or idea that the object pictured is supposed to suggest.

As you can see for yourself, the M-W definition isn’t especially clear. M-W states an ideogram is a picture or (emphasis added) a symbol. Additionally, the ideogram “represents not the object pictured” but “some thing or idea that the object pictured is supposed to suggest.” Perhaps such ambiguities are another cause of this perceived confusion.

We have agreed that, per Ingo Swann, the ideogram is the foundation for all CRV, yet we can’t find a definition in a dictionary that clearly states just what this foundation is. While Swann was not fond of neologisms (creating new words), in the case of the “ideogram,” he provided his students with what he considered an acceptable definition. For him, an ideogram:

- is the objectification or graphic representation of the psychic signal

- is a graphic representation representing the target’s primary gestalt(s)

- presents in sequential order from the main gestalt to greater and greater detail

- is represented in three parts: the ideogram, the feeling-motion, and the automatic analytical response

- contains all the necessary information in an encoded form to understand the target gestalt(s).

As I reflect on my years of being taught and mentored by Ingo Swann, (and 30 years of subsequent discussions), I realize Swann never taught me how to produce an ideogram; he taught me what an ideogram was, what it represented, and what to expect when “taking the coordinate …” Then it was my task to sit down, take the coordinate and produce an appropriate ideogram—spontaneously! When I sat down, I either produced an ideogram … or I didn’t. (Fortunately, I did.)

Remembering the success Puthoff and Targ had with skeptical visitors and how these visitors were able to produce “ideograms” before Swann knew what ideograms were, Swann provided me with his views on the ideogram and a pen and paper. The rest was up to me. Oh, surely he coached me along the way, especially for those first few weeks of producing ideograms, but he never told me what form of ideogram was supposed to represent water, land, or a manmade structure. He taught me that ideograms are unique to the viewer and to the target.

Swann taught that the viewer does not draw an ideogram. Drawing is a left-brained, analytic function. The ideogram is a spontaneous right-brained process; the ideogram produces itself. The viewer perceives an ideogram; the viewer receives an ideogram, or the viewer produces an ideogram, but the viewer does not draw an ideogram. The left brain analysis must remain disengaged. Drawing, tracing, and sketching are conscious, left-brained processes which can lead to analytical overlay.

Swann taught that the signal enters through the subconscious and the subliminal, and impacts the limen which is the threshold of one’s conscious awareness. When the signal impacts the limen, we objectify it by producing the ideogram.

Swann spoke of a pictolanguage or picture drawings. These are not a product of one’s artistic abilities in the usual sense. He stated that picture drawings drawn by gifted artists were “strikingly similar” to the drawings of non-artists, suggesting that they represent some form of subconscious picture language instead of an actual drawing. He called it “pictolanguage.” He said it incorporates information into basic forms and shapes, and that these forms and shapes are rarely fleshed out into highly artistic drawings. He said detailed drawings are a product of the conscious mind versus the picto-drawings of the unconscious mind. Picto-drawings are a kind of psychic imaging shorthand. Shape-form recognition takes place automatically—below conscious awareness. When initial, spontaneous shape-forms “pop out,” verbal descriptions may follow, but these verbal descriptions are a secondary response to the spontaneously drawn shape-form and may contain left-brained analysis. In other words, the picto-drawing is most likely correct, but the words that follow may be less correct or even incorrect.

I have had many discussions with many very good remote viewers who believe that the ideogram “looks like the target.” And while I will acknowledge that the ideogram often resembles the target, it can be misleading. While, at times, it may sometimes look like the target, according to Swann the ideogram always feels like the target.

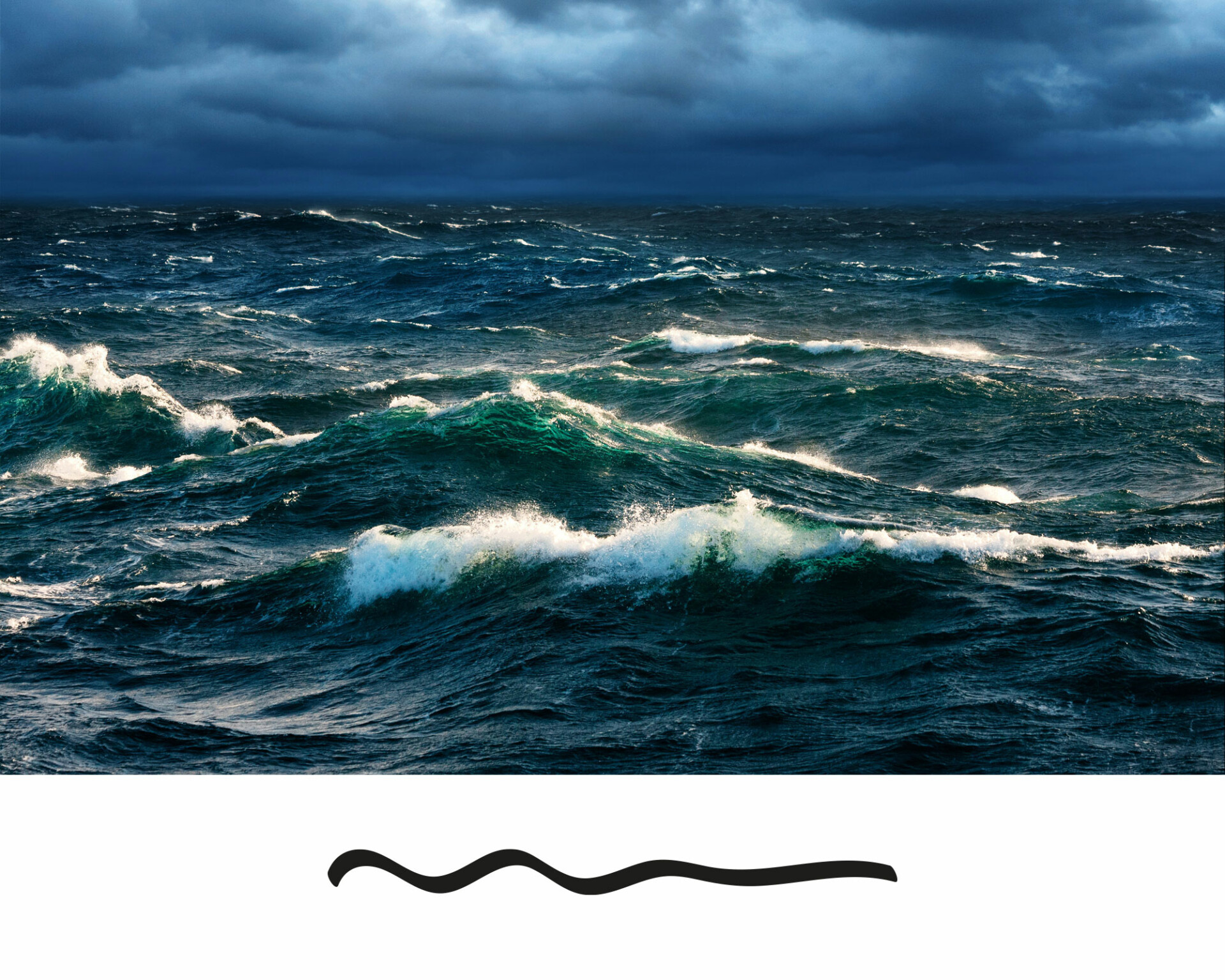

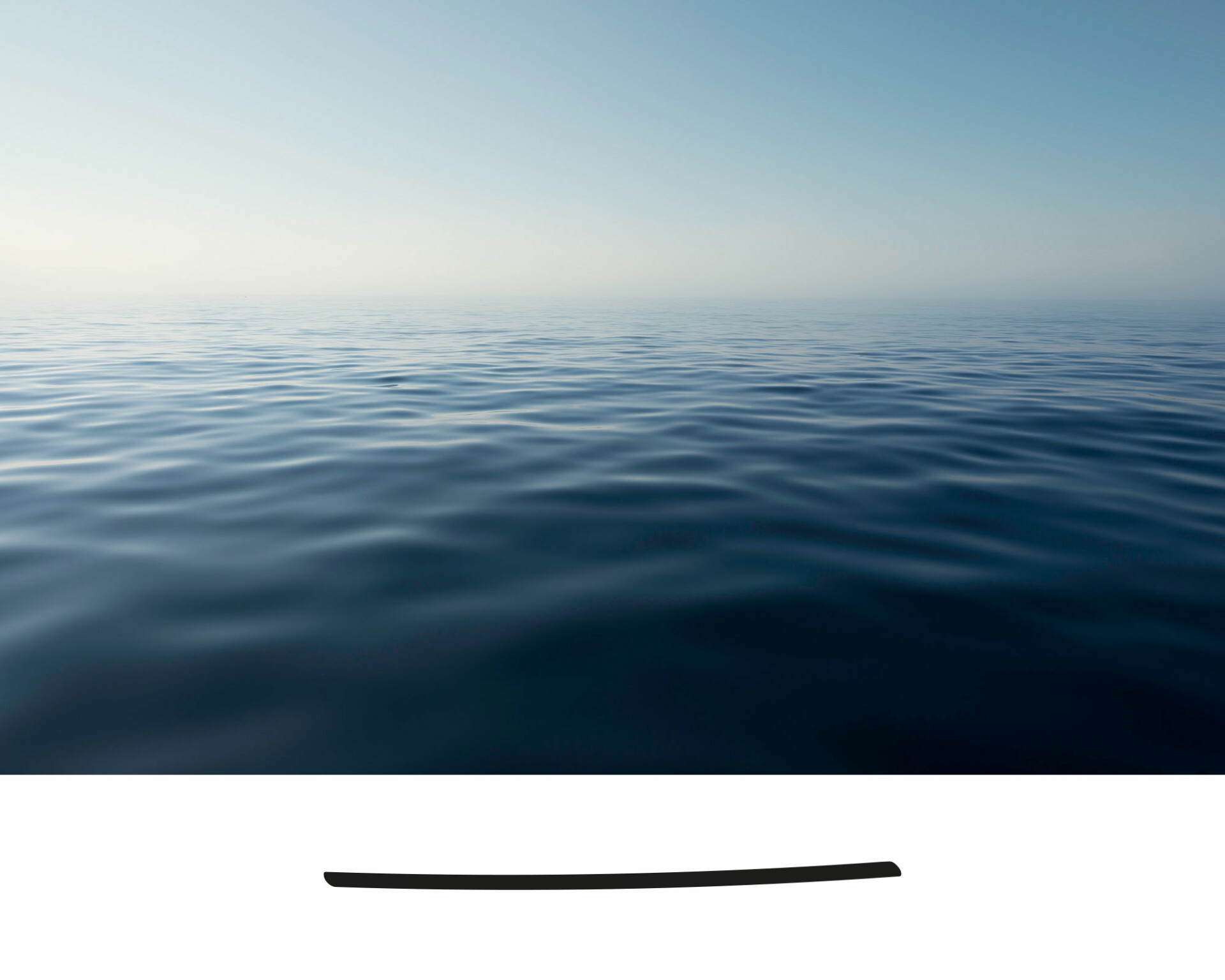

One very good viewer once told me that, for them, a flat line is always land. I acknowledged that a flat line is often land. I then asked what ideogram might they produce if the tasking number was in the middle of the Pacific Ocean on a very calm day—to which they responded, “well, I suppose it could be a flat line.” I then asked what would be the difference between a flat line representing land and a flat line representing water … well, of course, it’s the feeling-motion. Land would feel flat solid, water would feel flat fluid.

The lesson here is: don’t use the visual appearance to determine what the target is or what it looks like—use the feeling-motion. Remember, it was the feeling-motion that created the ideogram!

This lesson is especially important for visually ambiguous sites.

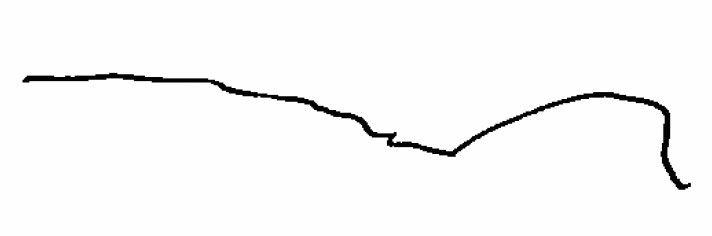

Looking at the above wavy-like ideogram, is it symbolic of water as in the lower picture, or does it represent the wavy land we see in the upper picture? How can a viewer tell the difference? It is the feeling-motion that will clearly differentiate between the two photos. Does the target, represented by the wavy line, feel fluid-like, or solid?

Again, looking at the following flat-line ideogram, does it represent the flat land of the first picture or the flat water of the second? It is the feeling motion which will allow the viewer to correctly decode the ideogram.

Just to be abundantly clear—since the point is an important one—consider the third curving-rounded ideogram. Does it represent the curving-rounded manmade structure in the first photo or the curving-rounded land/water interface in the second? It should now be obvious: it is the feeling-motion that reveals the nature of the target, and not what the mark on the paper “looks like.”

Did Ingo Swann Conduct Ideogram “Drills” With His Students?

A question I’m often asked is whether Ingo Swann conducted ideogram “drills” with his students. The answer is yes, but not for the reasons that so many think.

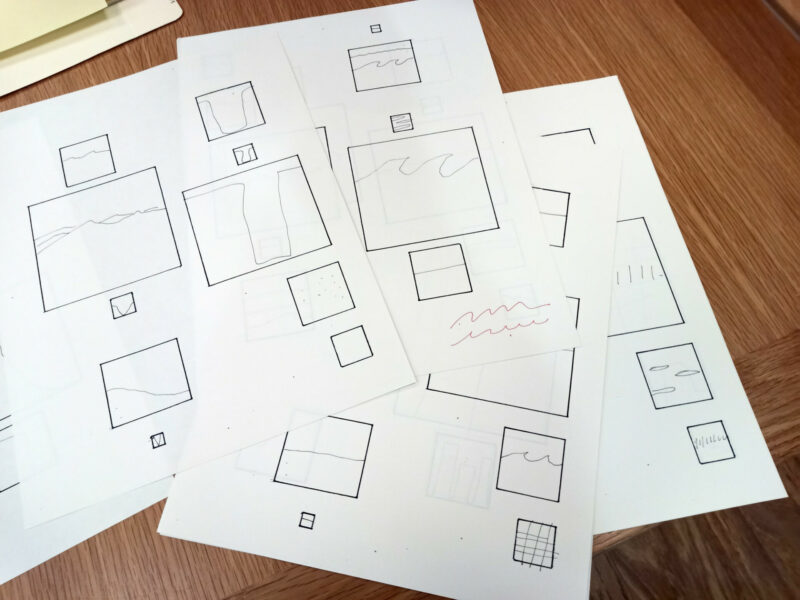

During Stage 1, when I first began producing ideograms, I tended to make wee small ideograms—many were less than one-half inch long. This did not please Ingo. He told me that larger ideograms were the product of more strongly experienced feeling-motions. He told me that I must produce larger ideograms to more fully experience the feeling-motion. After a continued period of producing less than the desired size ideograms, he said he had an idea. He pulled out unlined bond paper with a series of squares drawn on the page—some larger than others. He told me that he was going to call out to me geographic features like land, water, structure, mountain, etc. He said he didn’t care what the ideograms looked like; my task was to produce whatever ideogram came to mind, but it must span the size of the box, from top to bottom and from side to side (see below). In this way, he forced me to produce larger ideograms.

The purpose of Swann’s drills with me was to force me to produce larger ideograms. Today, some have perceived that these drills were intended to develop a standard ideogram for the features he was calling out. In other words, they believe that each time Swann called out water, I was to produce the same ideogram each time for water, or when he called out structure, I was to produce a standard ideogram for structure. This was not the intent of the ideogram drills during my time with Swann. The goal was not standard ideograms, the goal was larger ideograms.

Paul H. Smith said that during his time training with Swann, if Swann ever noticed that a student was “in a rut” and starting to make ideograms that looked like each other, he made them do ideogram “drills,” a conscious exercise designed to loosen up the production of unconscious ideograms. While this intent was somewhat different from my drills, Swann did not instruct them as to the appearance of the ideograms they produced, it was intended only to elicit a faster, more free-flowing ideogram in response to the target. As I stated above, Swann said that “every ideogram was unique,” and “no two ideograms were the same.”

Ideogram drills, from Ingo’s training of Paul H. Smith (1984)

What Did the CRV Manuals Say About the Ideogram?

Ingo Swann wrote little about the ideogram; consequently, the ideogram is not well addressed in the 1985 and 1986 CRV manuals. I wrote the first CRV manual in 1985 at the conclusion of my training with Swann. This document was entitled Coordinate Remote Viewing Stages I–VI and Beyond, February 1985. In 1986, when the program was transferred to the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA); Paul H. Smith and the other members of the program wrote a follow-on manual.

At the time both manuals were written, their purpose was to document or outline the Coordinate (later Controlled) Remote Viewing techniques being trained to the military members by Ingo Swann; neither manual was intended to be a “training manual.” Consequently, both manuals identified what ideograms were, what they represented, and what could be gleaned from them, but no effort was made to teach readers how to produce an ideogram or how exactly to work through the ideogram sequence.

Had we known that 30 years later students of CRV would find our manuals online and use them to teach themselves how to remote view, we would surely have written a more comprehensive “training manual.”

CRV by the Numbers

In Stage 1, Swann taught that the ideogram (I), the feeling-motion (the A), and the semi-automatic analytical response (the B) emerge from the right-brained subconscious. The steps in this process are:

- Receive the coordinate (tasking number) (usually from the monitor sitting at the other end of the table).

- The signal impacts the limen (the threshold of one’s conscious awareness).

- The impact of the signal on the subconscious spontaneously moves to the hand/arm producing an ideogram on the paper.

- The viewer describes the feeling-motion she/he experienced as the ideogram was being produced. This is labeled with an uppercase A.

- The viewer perceives an automatic analytic response to the combination of the ideogram and the feeling-motion. This automatic analytic response is labeled with an uppercase B.

As can be seen from above, this entire process emanates from the right-brained subconscious. And even though the B is called the automatic analytic response, this is essentially a jointly formed right/left-hemispheric subconscious analysis of the ideogram and the feeling-motion (I + A). If the viewer does not experience a spontaneous automatic sense of the site, the viewer should simply state “no B,” and take the tasking number again. If the viewer ponders the nature of the site and does not curtail the desire to provide an automatic analytical response, the higher order, left brain analysis will become engaged and will seek to provide a response. This left-brained response is based on fragmentary data and is the beginning of analytical overlay (AOL).

Summary

In this document, I have sought to explain what Ingo Swann taught me during the three years from 1982 to 1984. It was my goal to help readers understand that, while at first, the ideogram seems such a simple concept, only by comprehending its more complex aspects can viewers fully benefit from the data contained therein. Viewers can learn a great deal about the target from the simple I + A = B sequence. Accurately and fully decoding the initial ideogram(s) can establish a firm informational basis for the rest of the remote viewing session.

Controlled Remote Viewing is Ingo Swann’s legacy and his amazing gift to those who use it. His understanding of the ideogram, the way he taught it, and what it tells us about the capabilities of our subconscious is the gateway to Controlled Remote Viewing.

Thank you, Ingo!

Tom McNear at Ingo Swann’s Studio, New York, 2011

Footnotes

[1] Finally, in addition to my years with Ingo Swann, I must acknowledge that in the past 40 years I have learned a great deal from my many friends and colleagues in the CRV community. Some of the concepts and phrasing in this document may have come directly from discussions, readings, zoom conferences, etc. Where possible I have given credit to these people, but I wish to apologize in advance if I have inadvertently used the ideas or phrasing from these exchanges without giving due credit to the originator. Forty years is a long time and I am greatly challenged to remember what, and from whom, I may have learned. I am grateful to all who have contributed to my understanding and have contributed to the information contained herein; to them, I say thank you.

[2] Transcript of an unlisted audio recording made of a discussion between Paul H. Smith and Ingo Swann on December 1, 2010.

[3] This term was also coined by Ingo. After the project was declassified in late ’95, when remote viewing became a public issue, Ingo said that he had wanted to call it Controlled Remote Viewing all along, and that he preferred to use that term, and so everyone adopted it. (The Development of Controlled Remote Viewing (CRV), video recording of an interview between Dr. Harold E. Puthoff and Paul H. Smith from April, 2021.)

[4] Use of the term “analytical function” refers to the concept of the left brain (left hemisphere) and right brain (right hemisphere). Throughout this document, I refer to the basic intuitive functions of the subconscious as being right-brained or belonging to the right hemisphere of the brain, and I refer to analytic functions as being left-brained or belonging to the left hemisphere of the brain. While this is generally agreed upon by many scientists, psychologists, neurologists, and remote viewers, it is an oversimplification that some readers may question. For this discussion of the ideogram, I will not get involved in the left brain, right brain debate.

[5] We should think of the “feeling-motion” as being an intrinsic part of the ideogram since, in fact, it is the feeling-motion that impacts the viewer’s hand as it holds the pen to paper that produces the visible trace of the ideogram. Though they happen virtually simultaneously, the ideogram is the result of the feeling-motion experience, and not the other way around. (Similar to how the kinetic movement of the earth is recorded by the ink stylus on the seismograph paper when an earthquake occurs.) The subsequent written decoding of this feeling-motion into the two elements that comprise the A-component is a consciously-performed process by the viewer. Thus, the written, two-part A-component recorded on paper is not itself a part of the ideogram; it is merely the “objectification” the viewer produces of the experience he or she just had while creating the visible trace of the ideogram—even though it is still referred to as “the feeling-motion.” And just as an earthquake happens whether or not there is an ink-trace on a seismograph drum, an ideogram may be experienced even if there is no pen held to paper. Sometimes, after taking the coordinate, if the viewer is too slow in putting pen to paper, the ideogram is produced in the air. In such an event, the viewer may experience the feeling but will fail to record the motion on paper.

[6] Many tend to separate analysis (left-brained) from intuition (right-brained), but Swann believed that right-brained intuition possessed the ability to perform rudimentary decision making.

[7] Message from Ingo Swann to Daz Smith, 27 December 2007.